Asymptotic analysis

In mathematical analysis, asymptotic analysis is a method of describing limiting behavior. The methodology has applications across science. Examples are

- in computer science in the analysis of algorithms, considering the performance of algorithms when applied to very large input datasets

- the behavior of physical systems when they are very large.

The simplest example is, when considering a function f(n), there is a need to describe its properties when n becomes very large. Thus, if f(n) = n2+3n, the term 3n becomes insignificant compared to n2 when n is very large. The function "f(n) is said to be asymptotically equivalent to n2 as n → ∞", and this is written symbolically as f(n) ~ n2.

Contents |

Definition

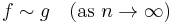

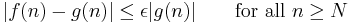

Formally, given complex-valued functions f and g of a natural number variable n, one writes

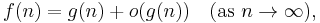

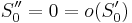

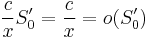

to express the fact, stated terms of little-o notation, that

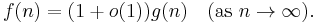

or equivalently

Explicitly this means that for every positive constant ε there exists a constant N such that

.

.

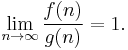

Unless g(n) is infinitely often zero (which would make the limit below undefined), this statement is also equivalent to

This relation is an equivalence relation on the set of functions of n. The equivalence class of f informally consists of all functions g which are approximately equal to f in a relative sense, in the limit.

Asymptotic expansion

An asymptotic expansion of a function f(x) is in practice an expression of that function in terms of a series, the partial sums of which do not necessarily converge, but such that taking any initial partial sum provides an asymptotic formula for f. The idea is that successive terms provide a more and more accurate description of the order of growth of f. An example is Stirling's approximation.

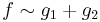

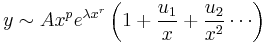

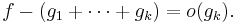

In symbols, it means we have

but also

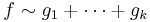

and

for each fixed k, while some limit is taken, usually with the requirement that gk+1 = o(gk), which means the (gk) form an asymptotic scale. The requirement that the successive sums improve the approximation may then be expressed as

In case the asymptotic expansion does not converge, for any particular value of the argument there will be a particular partial sum which provides the best approximation and adding additional terms will decrease the accuracy. However, this optimal partial sum will usually have more terms as the argument approaches the limit value.

Asymptotic expansions typically arise in the approximation of certain integrals (Laplace's method, saddle-point method, method of steepest descent) or in the approximation of probability distributions (Edgeworth series). The famous Feynman graphs in quantum field theory are another example of asymptotic expansions which often do not converge.

Use in applied mathematics

Asymptotic analysis is a key tool for exploring the ordinary and partial differential equations which arise in the mathematical modelling of real-world phenomena.[1] An illustrative example is the derivation of the boundary layer equations from the full Navier-Stokes equations governing fluid flow. In many cases, the asymptotic expansion is in power of a small parameter,  : in the boundary layer case, this is the nondimensional ratio of the boundary layer thickness to a typical lengthscale of the problem. Indeed, applications of asymptotic analysis in mathematical modelling often[1] centre around a nondimensional parameter which has been shown, or assumed, to be small through a consideration of the scales of the problem at hand.

: in the boundary layer case, this is the nondimensional ratio of the boundary layer thickness to a typical lengthscale of the problem. Indeed, applications of asymptotic analysis in mathematical modelling often[1] centre around a nondimensional parameter which has been shown, or assumed, to be small through a consideration of the scales of the problem at hand.

Method of dominant balance

The method of dominant balance is used to determine the asymptotic behavior of solutions to an ODE without solving it. The process is iterative in that the result obtained by performing the method once can be used as input when the method is repeated, to obtain as many terms in the asymptotic expansion as desired.

The process is as follows:

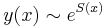

1. Assume that the asymptotic behavior has the form

-

.

.

2. Make a clever guess as to which terms in the ODE may be negligible in the limit we are interested in.

3. Drop those terms and solve the resulting ODE.

4. Check that the solution is consistent with step 2. If this is the case, then we have the controlling factor of the asymptotic behavior. Otherwise, we need to try dropping different terms in step 2.

5. Repeat the process using our result as the first term of the solution.

Example

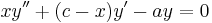

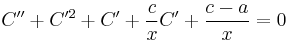

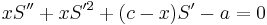

Consider this second order ODE:

-

- where c and a are arbitrary constants.

This differential equation cannot be solved exactly. However, it may be useful to know how the solutions behave for large x.

We start by assuming  as

as  . We do this with the benefit of hindsight, to make things quicker. Since we only care about the behavior of y in the large x limit, we set y equal to

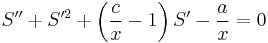

. We do this with the benefit of hindsight, to make things quicker. Since we only care about the behavior of y in the large x limit, we set y equal to  , and re-express the ODE in terms of S(x):

, and re-express the ODE in terms of S(x):

-

, or

, or

-

- where we have used the product rule and chain rule to find the derivatives of y.

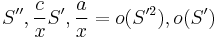

Now let us suppose that a solution to this new ODE satisfies

-

as

as

-

as

as

We get the dominant asymptotic behaviour by setting

If  satisfies the above asymptotic conditions, then everything is consistent. The terms we dropped will indeed have been negligible with respect to the ones we kept.

satisfies the above asymptotic conditions, then everything is consistent. The terms we dropped will indeed have been negligible with respect to the ones we kept.  is not a solution to the ODE for S, but it represents the dominant asymptotic behaviour, which is what we are interested in. Let us check that this choice for

is not a solution to the ODE for S, but it represents the dominant asymptotic behaviour, which is what we are interested in. Let us check that this choice for  is consistent:

is consistent:

Everything is indeed consistent. Thus we find the dominant asymptotic behaviour of a solution to our ODE:

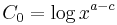

By convention, the asymptotic series is written as:

so to get at least the first term of this series we have to do another step to see if there is a power of x out the front.

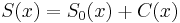

We proceed by making an ansatz that we can write

and then attempt to find asymptotic solutions for C(x). Substituting into the ODE for S(x) we find

Repeating the same process as before, we keep C' and (c-a)/x and find that

The leading asymptotic behaviour is therefore

See also

References

- ^ a b S. Howison, Practical Applied Mathematics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005. ISBN 0-521-60369-2

- J. P. Boyd, "The Devil's Invention: asymptotic, superasymptotic and hyperasymptotic series", Acta Applicandae Mathematicae, 56: 1-98 (1999). Preprint.

- A. Erdélyi, Asymptotic Expansions. New York: Dover, 1987.